Iran’s ‘Revolution of Values’: Living in a Theocracy

As I settled into the plane flying us between two Iranian towns, the pilot announced, "In the name of God the compassionate and merciful, we welcome you to this flight. Now fasten your seatbelts."

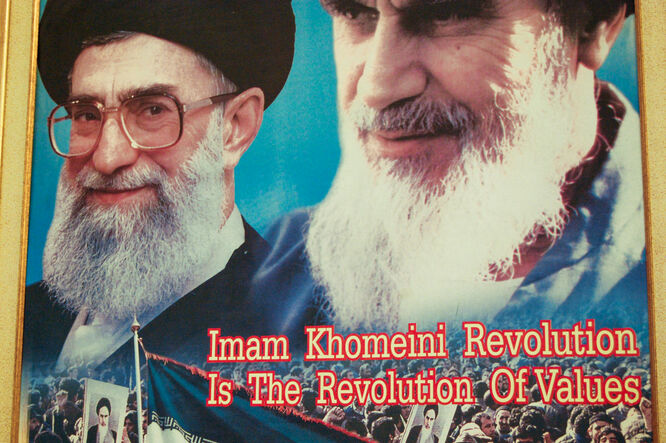

Whether on a plane, or simply walking the streets of any city here, it's clear that Iran is ruled by a theocracy. Even though it's technically a "Shia democracy" with an elected president, the top cleric—a man called the "Supreme Leader"—has the ultimate authority. His picture (not the president's) is everywhere.

The seeds of today's Iran were sowed during the Islamic Revolution in 1979. The rebellion, with its spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini, overthrew the US-backed Shah and took 52 Americans hostage for 444 days. As a gang of students captured the world's attention by insulting the US, this was a great event for the revolutionaries…and a wrenching one for Americans.

The US Embassy where the crisis took place was a stop on our filming route. Our guide, Seyed, seemed almost proud to let us walk the long wall of anti-American murals. He encouraged us to film it, making sure we knew when the light is best for the camera.

As I walked along the wall, it occurred to me that this national humiliation happened three decades ago. While it remains a sore spot for many Americans, Iranians—two-thirds of whom weren't even born at the time—seem happy to let the murals fade in the sun. Today the murals drone on like an unwanted call to battle...a call that people I have encountered have simply stopped hearing. (Looking back, many Iranians believe that the hostage crisis hijacked their Revolution, radicalizing their country and putting things in the hands of the more hard-line clerics.)

Thirty years on, the Islamic Revolution has become deeply ingrained. After chatting with one young man who didn't look as if he was particularly in compliance with the Revolution, we say goodbye. Later—after he'd thought about our conversation—he returned to tell me, "One present from you to me, please. You must read Quran. Is good. No politics." Looking at the evangelical zeal in his eyes, I realized that he had just as earnest a concern for my soul as a pair of well-dressed Mormons who might stop me on the street back home. Why should a Muslim evangelist be any more surprising (or annoying, or menacing) than a Christian one?

Seeing the Ayatollah Khomeini from the Iranian perspective was jarring: Rather than the impression I've long held—of a threatening ideologue—many Iranians consider Khomeini a lovable sage...unpretentious, approachable and a defender of traditional values. After the Shah's excesses and corruption, Khomeini's simplicity and holiness had a strong appeal to the masses. Locals tell me that Khomeini had charisma, and if he walked into a room, even I, a non-Muslim, would feel it. To the poor and the simple country folk, Khomeini was like a messiah. As the personification of the Islamic Revolution, he symbolized deliverance from the economic and cultural oppression of the Shah. Khomeini gave millions of Iranians hope. Khomeini's successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has had much less of an impact on the people. (I imagine Shia Muslims miss Khomeini like Catholics miss John Paul II.)

Iranians who support the Revolution call it a "Revolution of Values." Many conservative Iranians I met told me they want to raise their children without cheap sex, disrespectful clothing, drug abuse, and materialism—all things they associate with America, and all things that, they believe, erode character and threaten their traditional values. It worries them as parents. It seems to me they willingly trade democracy and political freedom for a society free of Western values (or, they'd say, "lack of values"). It's more important to them to have a place to raise their children that fits their faith and their cherished notion of "family values."

Of course, there's plenty of drug addiction, materialism, and casual sex in Iran—but these vices are pretty well hidden, and are constantly being rooted out by the theocracy. In general, the Revolution seems to be well-established. In terms of materialism, Iran and the US stand at opposite extremes. Back home, just about everywhere we look, we are inundated by advertising encouraging us to consume. Airports are paid to drone commercials on loud TVs. Magazines are beefy with slick ads. Sports stars wear corporate logos. Our media are shaped and driven by corporate marketing. But in Iran, Islam reigns. Billboards, Muzak, TV programming, and young people's education all trumpet the teachings of great Shia holy men...at the expense of the economy. (Consequently, many in Iranian society tune into Western media via satellites and the Internet, and barely watch Iranian media.)

And yet, I am surprised by the general mellowness of the atmosphere in Iran compared to other Muslim countries. Except for the strict women's dress codes and the lack of American products and businesses (because of the US embargo), life on the streets here is much the same as in secular cities elsewhere. Ironically, despite the aggressively theocratic society, the country actually feels less spiritual than neighboring, secular Muslim nations I've visited. In Turkey, it can be hard to walk down the sidewalk during prayer times because mosques are overflowing with people. In Iran, I have barely heard a call to prayer, and almost no spikey minarets break the skyline.

While the focus of my trip is on the people rather than the politics, Iran's theocracy makes civil rights concerns unavoidable. Civil liberties for women, religious minorities, and critics of the government are the mark of any modern, free, and sustainable democracy. I believe that, given time and a chance to evolve on their cultural terms, the will of any people ultimately prevails. But in Iran, that time is not yet here. For now, this country is not free. (And no one here claims it is—locals like to say, "Iranian democracy: You are given lots of options...and then our government makes your choice for you.") A creepiness that comes with a "big brother" government pervades the place. Every day during my visit, I wondered how free-minded people cope.

While the Islamic Republic of Iran's constitution does not separate mosque and state, it does allow for other religions...with provisions. I asked my guide, Seyed, if you must be religious here. He said, "In Iran, you can be whatever religion you like, as long as it is not offensive to Islam." Christian? "Sure." Jewish? "Sure." Bahá'i? "No. We believe Muhammad—who came in the seventh century—was the last prophet, and the Bahá'i prophet came in the 19th century. The Bahá'i faith is offensive to Islam and therefore not allowed."

I asked, "But what if you want to get somewhere in the military or government?" Seyed answered, "Then you'd better be a Muslim." I added, "A practicing Shia Muslim?" He said, "Yes."