Pamplona’s Running of the Bulls

By Rick Steves

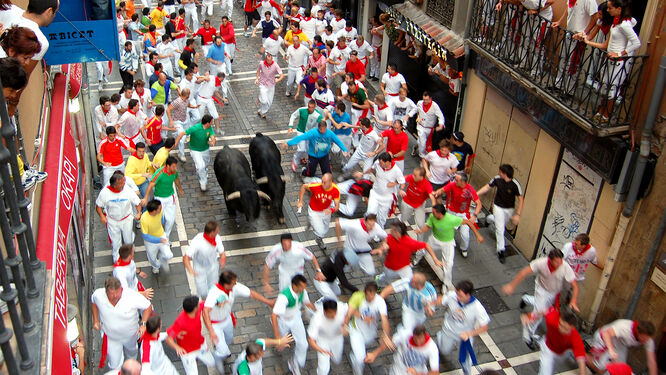

Each July, a million revelers pack into Pamplona, Spain, for the raucous Festival of San Fermín. They come to this proud town in the Pyrenees foothills for music, fireworks, and merrymaking. But most of all, they come for the Running of the Bulls, when fearless (or foolish) adventurers — called mozos — thrust themselves into the path of six furious bulls.

Originally celebrated as a saint's feast day, the festival now runs for nine days, from July 6 through 14. Each morning at 8 o'clock, the bulls are set loose on the city streets with Spaniards across that nation following every twist and turn on live television.

Mozos, like Spanish bullfighting aficionados, respect the bull. The animal represents power, life, the great wild. Ernest Hemingway, who first came to the festival in 1923, understood. He wrote that he enjoyed watching two wild animals run together — one on two legs, the other on four.

Although they can wear anything, mozos traditionally dress in white pants and shirts, with red bandanas tied around their necks and waists. Two legends explain the red-and-white uniform: One says it’s to honor San Fermín, a saint (white) who was martyred (red); the other says that the runners dress like the butchers who began this tradition. (The bulls are color-blind, so they don’t care.)

A wave of energy surges through the streets each morning as the start time approaches. My film crew and I were at a recent festival, stationed at a vantage point along a sturdy barrier where the bulls would go blurring by. (The event unfurls so quickly that we filmed it on two mornings to get enough footage.) Every morning, spectators start assembling at the crack of dawn. For many of these revelers, early morning is just the tail end of a night of partying.

As onlookers pack the side alleys, the mozos jockey for a favorable position on the street. For serious runners, this is like surfing: You hope to catch a good wave and ride it. A good run lasts only 15 or 20 seconds. You know you are really running with the bull when you feel the breath of the animal on your pants.

Then it's time, and the sound of a rocket signals that the bulls are running. Resembling hundreds of pogo sticks, a sea of runners spontaneously begins jumping up and down — trying to see the rampaging bulls to time their flight.

Like a freak wave pummeling a beach, the bulls rush through. It's a red-and-white cauldron of desperation. Big eyes, scrambling bodies, the ground quaking. As the bulls charge down the street, the mozos scramble to stay out in front of the thundering herd, diving out of the way at the last possible moment.

A bull becomes most dangerous when separated from the herd. For this reason, a few steer — who are calmer and slower — are released with the bulls. There’s no greater embarrassment in this machismo culture than to think you’ve run with a bull, only to realize later that you actually ran with a steer.

Then, suddenly, the bulls are gone. People pick themselves up, and it's over. Boarded-up shops open up, and the timber fences are taken down and stacked. As is the ritual, participants drop into a bar immediately after the running, have breakfast, and together watch the rerun of the entire spectacle on TV — all 131 seconds of it.

Each year, dozens of people are gored, trampled, or otherwise injured during the event. A mozo who falls should never get up — it's better to be trampled by six bulls than to be gored by one. While 15 runners have been killed by bulls over the last century, far more festival-goers have been impaired from overconsumption of alcohol. The festival means party time in Pamplona.

It's fun to follow along in the actual foot-and hoof-steps of the participants. From the bull corral where the bulls are released to the bullring, the route is marked by signs. One of the most hair-raising points is at the turn into the street named La Estafeta, where the running bulls begin heading downhill, often losing their balance and sliding into the barricades. When the bulls aren't running, La Estafeta is one of the most appealing streets in Pamplona, home to some of the best tapas bars in town.

When the rollicking festival concludes at midnight on July 14, Pomplona's townspeople congregate in front of City Hall, light candles, and sing their sad song, "Pobre de Mí:" "Poor me, the Fiesta de San Fermín has ended."